Yes, this is a little bit about Covid. It’s also a little bit about wetlands and a little bit about snakes and a little bit about a dead rabbit in the road.

I have two bumper stickers on my car. One says “Please Brake For Turtles” and one says “Please Brake For Snakes”. While strangers often ask me about my turtle sticker — where did I get it, how they move turtles off the road, etc — the snake sticker gets no such love. Occassionally, it gets hate.

The other day, I had to pick up a package at the post office. When I came back to my car, there was an older woman standing at my bumper, shaking her head. She had come to the post office to pick up her mail. She went to get into her car, but as I went to get into mine, she stopped to call out, “The only good snake is a dead snake!”

It’s not the first time. I was still wearing my mask so I made sure my smile reached my eyes as I said, “Well I like’em.” She was not finished though. She explained that while she can see that I am a snake lover, she has a friend who has a snake and her friend is forever trying to get this lady to come over and see it. The woman was quite clearly afraid of snakes. But all she could express with that fear was snakes bad. I suggested that perhaps we could agree that snakes belong in the wild. Yes, she said. Snakes in the wild is okay.

The problem with this knee-jerk response, this good/bad animal dividing line, is that it ultimately threatens all animals, and especially there being any sort of “wild” left for any animal to be in. Grasslands with boardwalks on a sunny day are “good”, but not those muddy yucky wetlands in the rain. What animals know, what we humans seem perpetually unable to grasp, is that we are all of us wildly and deeply connected. On good days and bad. The aesthetically pleasing, and the challenging. Scavengers and carnivores and omnivores and carrion-eaters, up and down and side to side in nature’s intricate webs. In woods and wetlands and hills and grasses and streams and cities. It all exists together. We exist together. Or we don’t exist at all.

Covid has reminded us that our fate as humans is primally, internationally, inextricably, bound up in each other. That our choices can endanger or protect. It has also reminded us that we are a part of nature, and that we release our worries and soothe our stress by spending time in it.

Yet right in the middle of Covid, in the middle of one of the most stressful life events many Ontarians have experienced, Ford’s provincial government snuck through law that took away the ‘authority’ part of Conservation Authorities.

They literally made it easier to pave paradise and put up a parking lot.

“As one example of the consequence of this change, it is now expected that a development company whose owner donated thousands of dollars to the Ontario PC Party will be able to pave over a 57-acre lot in the Toronto suburb of Pickering that is under protection as a ‘provincially significant wetland,’ and build a distribution centre.”

~ Globe and Mail Editorial

Poor Conservation Authorities. On top of everything, they really suffer from a branding problem. Neither of the words that make up their name sounds appealing. While “conservation” is admirable, the word itself has strong conservative connotations. A sense of holding on to something, a stubborn unwillingness to move forward. With something good like, say, “development”. “Authority” is even worse. Humans have a natural resistance to too much authority. It sounds like the worst kind of unneccesary red-tape. Ugh, more authorities to go through!

(It’s an inverse case to how “landfill” uses its name to sneak under the radar as a not-really-so-bad a thing. It sounds like something that needs doing, doesn’t it? It was empty, and so we filled it. Well done us. Pass the disposable everythings.)

What Conservation Authorities do in practice is safeguard both the now and the future of our water, woods and wetlands — for you, for me, and for everyone yet to come. The habitat for both the turtles and the snakes. And the humans.

“While Canada holds 25% of the world’s wetlands, we have already lost 70% of them over the last century, due to human development. Often turtles are the biggest biomass in these wetland ecosystems. The loss of biodiversity and degradation of ecosystems has unpredictable effects, but they are always negative. The web of life depends on all components, and just like in the game ‘Jenga’, a loss of a critical mass will lead to complete collapse. Why should we care about wetlands? Wetlands are essential for us as humans too! Wetlands act as the ‘kidneys’ or the filtration system of our water source- unhealthy wetlands means an unhealthy water source.”

~ Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre

It is not just the cute and the beloved that needs care, that matters. Just as it is not only the beloved grandmother we are trying to get safely to the other side of our tangles with this virus. It is also the vulnerable we see and don’t see. It is also the lady who wants to argue with me about snakes. The stranger I do not know may be the person who makes life worth living for someone else. I try hard to notice what I don’t see. To care about not only what is in front of me, what is easy. Out of sight out of mind. I succeed and I fail, but I try.

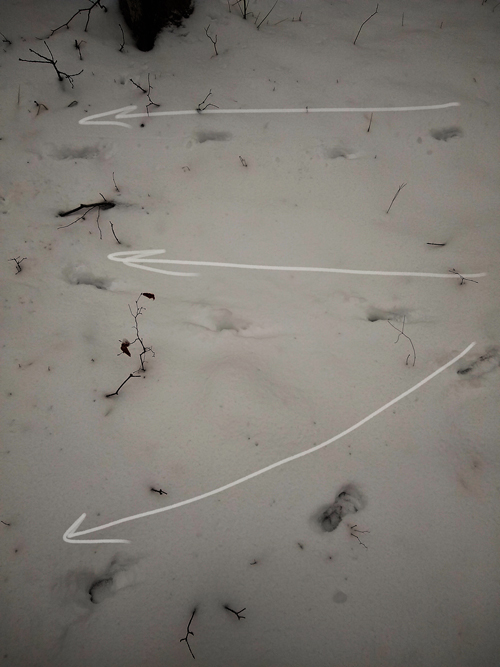

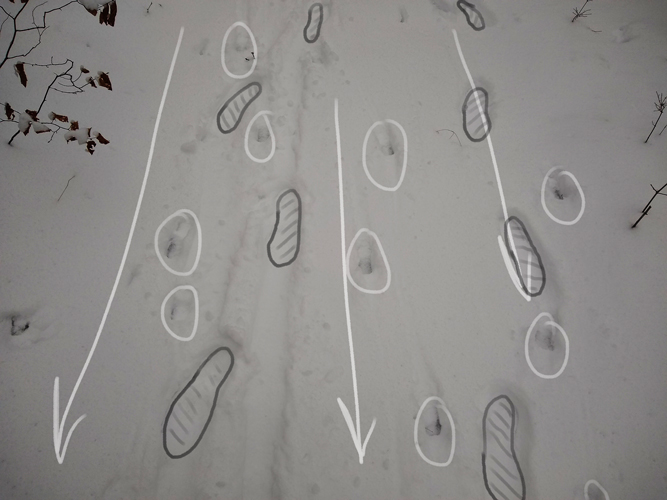

Leaving the post office, I took a quiet road home. Coming over a rise in the road, I saw a dead rabbit in the road. It had been hit by a car and was very dead. It was also very much in the road. Though being in the road was no further danger to the rabbit, it was not safe to leave it there. It can lead to future drivers feeling they need to swerve, uncertain what they are seeing. Tire tracks in the snow showed this was already the case. But it also poses a danger to the wildlife who will inevitably come to feed on it. The scavengers and carrion-eaters who each play their own role in nature’s web — not least of which, cleaning up our messes.

I found a safe spot to pull over, stopped, and moved the bunny off the road. Though that seems gruesome to some, it is a last act of caring. Both to show respect for the life that was lost, and giving a greater chance to the other creatures. The unseen creatures. The life in front of me, and the lives I don’t see. Snakes and turtles. The beloved and the stranger. It all matters.

~Kate

Oh… Oh my.

Oh… Oh my.

Chickens: “Thanks Bipedal Female Food-And-Water Dispenser, but do you have anything with more dirt in it? ktks”

Chickens: “Thanks Bipedal Female Food-And-Water Dispenser, but do you have anything with more dirt in it? ktks”