For each question I answer in the woods, five more appear. “Solved” tracks are surrounded by stories I haven’t read, and some where I don’t even know the language. I am getting better at recognizing animal tracks and sign. I can usually narrow things down so we’re at least pointed in a helpful direction. But I have so much to learn. If I have the shapes, do I have the movements, if I have the movements, do I have the “when”… It goes on and on forever. I know that I will never be done learning, and that is fine with me. I hope I will never be done learning. I love to solve a puzzle, and work a problem. But I have no illusions the puzzles will ever end. The only constant is change. Besides, as John Hodgman said, “beginnings are really the only happy endings”.

I did an undergraduate degree in Philosophy, with extra attention to the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Philosophy is not where I started off in school, but it is where I ended up. Because philosophy contained the most “whys”.

Philosophy let me dip my toes in the most worlds. I could study advertising and environmental ethics. Nuclear bombs and modern symbolic logic. Darwin and art and how the brain works and it was all the same degree.

That’s a little explanation for my love of the “why”. It runs wide and deep. Why is this here. Why is it this shape, in this place, at this time. In tracking I am always skating between the known and the unknown. Being curious, and being methodical. Confidently working the puzzle, but reigning myself in if/when I get too rash or brash. Keeping an eye on my assumptions. Not thinking I have all the answers, but not getting so stuck in the questions that I can’t move forward.

Here is a short piece of an unfinished story. One of so many unanswered whys.

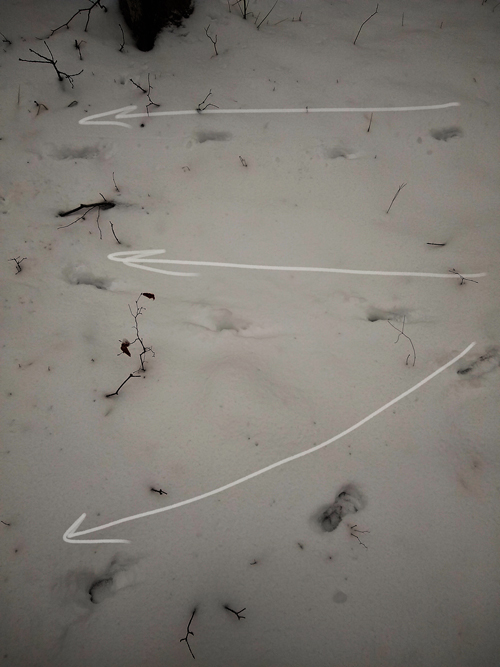

I came across this opening in the snow the other day. It is a small opening, in a grassy part of our property. I found it while following fox tracks, and was surprised by what I saw. Though it seemed to be a little hole for a little rodent, the fox tracks didn’t even seem to pause. Mice make up a good sized part of a fox’s winter diet. So why had this fox gone right past this hole?

Perhaps it hadn’t. Though both tracks had been made since the last snowfall, perhaps it was at different enough times that one wasn’t aware of the other. But also… why was there scat and urine at the opening of the hole? Isn’t that a bit, well, brazen? In a world so affected by smells, so full of critters who can and do literally sniff you out, why would you leave such a signpost on your doorstep?: “Here there be noms.”

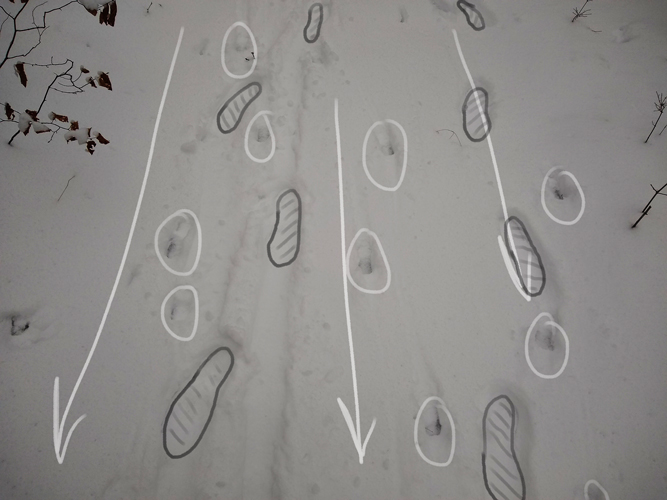

I am not yet able to tell the difference between the tracks of shrew/vole/mice, unless there is some “gimme” to make it obvious. Like these wonderful gimme tracks in our woods, where the mouse very kindly left clear tails print in the snow.

As I said, we have mice and voles and shrews here (at least). They each leave slightly different tracks and sign. For my money, this scat and tracks were a bit different than a mouse’s. Pushing us more into vole/shrew territory. Or some other wee rodent/insectivore I did not think to think of.

Maybe, I thought, maybe the fox walked past because it didn’t want what was in that hole. And maybe there is a reason the critter who made the hole wasn’t too worried about being found?

Shrews are small insectivores. They are similar in size and shape to mice, except with more of an anteater-style snout. They look a bit like a mouse that got its face stuck in a vaccuum cleaner. One day while out for a walk, I found a dead shrew in our woods. Specfically, and importantly, I found a killed but uneaten shrew in the woods. Before I learned more about shrews, I wondered why on earth critters would pass up a morsel of protein like that?

As is often the case, it’s because the critters knew more than I did. Apparently shrews don’t taste very good. They produce a potent venom in their saliva, making them one of those rare beasts: a venomous mammal. Though foxes and other animals will kill and sometimes eat them, they’re not first on everyone’s menu. And apparently that bite hurts. (Yes, even for us humans. Shrews are best left untamed.)

Like I said, I don’t have an answer for this particular puzzle. It might be a shrew, it might not. We just have some pieces and plenty of “whys”.

Alongside the “whys”, here are a few things we do know:

- the scat was left, along with what appears to be urine, at an opening to a tunnel

- the tunnel appears to be in the “subnivean” layer. Literally meaning “under snow”, subnivean is the area above the surface of the ground and below the surface of the snow. Mice, voles, and shrews all use this layer as winter habitat. (Once, on a a truly magical winter walk, I walked past a snowy spot where I heard some scurrying around. Still one of my favourite memories.)

- Though the timing is a mystery to me, both this creature and a fox used the same area. Either the fox went through and then the little critter moved in, or the little critter was already there when the fox went through.

What happened when, and what that critter was… I don’t yet have an answer. I could have dug into the tunnel to try and find out who lived there, some trackers do. But my curiousity has limits, and digging up another critters’ home, to satisfy an idle “why”, is on the other side of them.

T.S. Eliot wrote:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

I’ve always enjoyed that poem. But I think this short stanza is too long to happen within a human’s life. We’ll never meet the end of our exploring. The place is too rich, too full of mysteries, too full of whys. I’ll go back to where I started, and I will know the place a little better. But the exploring, that never ends.